You’re a jerk

Nothing’s new under the sun, but listeners really don’t like new music right now. The algorithm has so obfuscated the search for deep connection to music that old tunes now command 69.8% of the on-demand record market, a 7% increase since 2020.

(It's important to note this trend also reflects the plot of legacy copyright hoarders who intend on turning every cherished hit into a Swiffer commercial. Read about that part here.)

In our nostalgic yearning for shared histories to unite present separations, we’ve brought Jerkin back, the dance style and music genre that, in its time, presented a bonafide counterculture within and alternative to a mainstream plagued by violence.

How did Jerkin, a movement at once dismissed by both its local gangbanging roots and its alternative rap peers when it started nearly two decades ago, come to represent a beacon of positivity in present day rap? The answer lies in the Los Angeles metropolitan roots of jerk music, the irrational escalation of commitments that has defined the modern rap era, and the dynamic spirit of a Black culture that continues to redefine itself.

Whether through TikTok, Fortnite, or some yet unimagined medium, the jerk — and other local-turned-global inventions like Chicago footwork or Philly tangin — will continue to retrend in a cultural environment in which social media has shrunk trend cycles to pico-scale, with marginal updates to established sounds enough to create new waves. Consumer media has always wielded nostalgia as a weapon in the pop culture marketing (propaganda) battlefield. But unlike Tyga redoing “Ice Ice Baby,” Jerkin in particular wins a bottom-up victory highlighting the shift in what we consider positive rap.

Conscious vs positive rap

Today’s positive rap hardly resembles the “conscious rap” De La Soul and A Tribe Called Quest brought to the masses three decades ago, nor does it pledge allegiance to “The Message.”

The “conscious” label described a rap subgenre that spoke to social and interpersonal struggle, to raise listener awareness of global issues and ultimately energize individual and collective action towards solutions. While hip-hop with that intent still exists for those who seek it, its presence in mainstream rap is rare once you move past Kendrick. Conscious hip-hop often considers the sonic originality and aesthetic experimentation of avant garde production, whether elegant flips, interstellar jazz, or the latest digital instrument. The soundscape is fundamental to existential exploration, verbalized through lyrics. The late jazz legend Weldon Irvine played keys on the opening of “Mos Def and Talib Kweli are Black Star,” followed on the next track by the duo lamenting the rise of violence in hip-hop at the time: “It's kinda dangerous to be a MC/They shot 2Pac and Biggie/Too much violence in hip-hop.”

The initial rise of conscious hip-hop in the late ‘80s followed a long run of rap that promoted partying and #vibes— a bacchanalian, celebratory lyrical theme alone did not meet the criteria for the “conscious” label. As much as Will Smith congratulated himself for not cursing, “Welcome to Miami” wasn’t a conscious record. Recent years have seen the party/positive line blur.

Somewhere between Immortal Technique and Killer Mike, who, despite his long-beloved advocacy for a more equitable society, appeared alongside police during the 2020 uprisings to dissuade ATLiens from protesting, the political establishment co-opted various strains of hip-hop to maintain and promulgate its political project. Once considered radioactive for politicians, hip-hop has long acted as the litmus test for politicians’ “downness” with the culture; this conversely gives the political establishment a means of manufacturing consent from young and Black demographics through hip-hop. Even Trump had his moment in the sun when he took credit for the return of A$AP Rocky from a Swedish prison (Rocky later said Trump “made it a little worse.”)

On parallel tracks, the listening public has broadly rewarded rap that aims to soundtrack increasingly explicit violence, while condemnation awaits any artist who suggests that the Democratic party may not best serve Black peoples’ interests. The thesis of this year’s Hip-Hop at 50 documentary by PBS is that rap crossed the social consciousness finish line with the election of Obama as president. Meanwhile, Adam22, amplifier of so much cereal-for-breakfast music (and an alleged sexual abuser), is the son of a man pardoned by a previous Democratic president who oversaw the disastrous 1994 crime bill. It’s not insignificant that a gatekeeper pushing so much unhelpful music has family ties to Bill Clinton. Jay-Z performed for the other Clinton in support of her Democratic run in Ohio. Even today’s more activist-minded artists shy away from the original concerns of conscious hip-hop — class struggle, Afrocentrism, ruling class criminality or what some would call “conspiracy theory.” The most notable support for a progressive politician came not through music, but the tweets of superstar Cardi B, whose outspoken support of Bernie Sanders marked a rare break from the Democratic establishment.

During these hollow times, alignment with political causes no longer necessarily makes rap “conscious.” We define positive rap here as healthy rap — rap that influences beneficial, desirable outcomes in its audience. Ideally we would measure the quality of rap by its Use Value, not its exchange value on an anything-goes market, and not necessarily according to some Puritan standard of wholesomeness either. Without a scintilla of preachiness, Wiz Khalifa’s normalization of cannabis consumption made a tremendous positive impact shifting public attitudes toward legalization. Positive rap doesn’t have to be appropriate for children. However, when we talk to kids at the park today, they recognize talents like NBA Youngboy and Lil Durk not so much for their melodic skill, emotional weight, or ability to shine light on grim situations, but by the count of bodies piled on each side of their years long beef.

Side by side, the 2000s, 2010s, and 2020s evolutions of party rap start to look like a joyous alternative.

Jerkin, the party soundtrack for California’s coming of age millennial gangsters, anticipated rap’s spiral into increasingly violent content with a leftward tilt that ingeniously met the culture where it was at that time. The jerk movement, propelled by dance, personal video cameras, and early YouTube, likely saved many lives in the Los Angeles area and beyond. However, the mainstream would initially slap away jerkin’s outstretched hand (or foot).

Teach me how to jerk

The rise of Jerkin out of early 2000s Los Angeles provides one of the most relevant and revelatory vantage points from which to survey the shifting definition of positive rap.

On one hand, Jerkin emerged as a response to the dominance of LA’s gangsta rap tradition — in itself both a response to and commodification of mass incarceration. Compared to the justifiably aggressive and often offensive intent through-lining legends like N.W.A, The Game, Westside Connection, and The D.O.C., Jerkin offered a well-received outlet for alternative youth, alongside MCs like Murs and Blu. Jerkin dance moves like “the reject,” “the pindrop,” and “the spongebob” emphasized humor, uninhibited play, and nimble footwork, with its soundtrack composed of simple synths; sparse, heavy, detuned bass; and catchy hooks. Pristine production wasn’t a goal — Jerkin progenitor TayF3rd recalls recording his first hit in a Lucky Charms cereal box. The irreverent attitude of the jerk movement foreshadowed today’s expectations for underground and mainstream music alike.

On the other hand, many jerkers didn’t outright disavow gangbanging; they simply felt they could skateboard, take psychedelic drugs, and dance too. The fashion adapted the prevailing street attire — the same “hood emblems,” paired with “skinnies and designer” instead of “chucks and such.” “Jerking” itself originally described a lively party, possibly stemming from the involuntary movement symptoms of overdosing on x, like a southern California counterpart to the Bay Area’s “thizzing.”

From its inception, Jerkin was an ironic, contradictory subversion of the very culture it sought to resist, a gray area where one could be hard and also hip. Some out-group contemporaries initially labeled Jerkin wack, a violation of the Black cultural identity codes implied by the mainstream rap of the time. Jerkin generally got lumped in with the backlash from contemporary rap purists against millennium era dance-driven hip-hop like snap and crunk music largely coming out of the South. Back then I stayed glued to my desktop chair on alert for the latest Jerkin video upload or response, whether good, bad, or ugly. I saw message board comments deriding the dance move, contrasting it with the gang-affiliated C-walk, which they saw as more impressive. Tyler, the Creator spoke loudly in criticism of Jerkin, famously rapping “I ain’t with that Jerkin shit” on his 2009 track “Tina.”

Despite these choppy waters, those who knew, knew: Jerkin was rooted in a contagious optimism. So long as rap prevalently displays morbid unreality — exaggerated street tales that kick start violent, self-fulfilling loops as a trauma response to state racism — Jerkin will persist. It might not have met the late, great Phife Dawg’s bar for “conscious rap,” but jerking grew out of the same core operating principles. Conscious rap drew from jazz, Jerkin from rave music. Both netted out to a constructive outlet with real day-to-day ripples.

“House parties were getting routinely shot up. LA and IE gang activity was at an all time high,” recalls JujuNVM, the half of legendary jerk duo Audio Push formerly known as Oktane. “Jerkin calmed EVERYBODY tf down…Kids EVERYWHERE from ALL kinda gangs was runnin up tryna have DANCE battles. Shit brought [genuine] peace for a minute.”

Starting in 2006 with moments like Tayf3rd’s “i smoke i drank i jerk” and Audio Push’s “Teach Me How to Jerk,” Jerkin would crossover from regional trend to national craze, fueled by YouTube uploads of kids doing the jerk on every high school blacktop and McDonald’s marquee in the United States. Going to high school in Orange County, California during the height of the jerk movement, I naturally photobombed some jerk filmings in progress, though I don’t think any of my moves made the final cut.

Some of these videos transcended their medium into cult classic films. Usually shot in found-footage style with a homemade quality, they depicted jerk troupes like the Power Rangers doing their dance on various road intersections and landmarks around Los Angeles. They signaled the youth’s reclamation of one of the world’s most human-hostile, physically disunified cities. If Los Angeles is unwalkable, the reject’s backward-yet-forward ambulation through LA streets amounts to a derivé unimagined by Debord in his psychogeographic studies.

Jerking amounts to one of the earliest internet-viral music subcultures that accelerated the metamodern state of rap. The movement captivated an entire generation, breaking stars like YG, Kid Ink, and Ty Dolla $ign from within its scene, and birthing reactions to the trend that led to the rise of artists like Lil B and Tyler, the Creator. The core reproduction mechanisms that Jerkin introduced — dancing recorded on personal cameras — now form the premise of today’s most relevant social media platforms, fronted by TikTok.

“People overlook it a lot, but it’s undeniable when you see the premise of TikTok, etc.,” Juju says. “It literally was exactly what social media is about today.We took a camera out, really danced in front of it. And the world did the same.”

Ground-level Jerkin originators like TayF3rd and Audio Push would expand and refine their artistic repertoire, working their way toward local legend status with national reach. Other than “Teach Me How to Jerk,” Audio Push’s next biggest hit would come in the form of their feature on Hit-Boy’s West Coast Anthem, “Grinding All My Life.” The posse cut, with no less than eight guest appearances, is not a jerk record; the performers in fact largely situate the song in the California gangster rap tropes jerking originally rebelled against. And while Audio Push doesn’t go out on a limb to force jerk rap onto the track, group member Juju’s contribution stands out: his first two lines, “fuck that, you’re hogging the mic, let me rap now / make some noise if you’re high right now” harkens back to the ironic humor and normalized drug use core to Jerkin.

Concurrent to jerking, other dance-based hip-hop movements imbued a similar ethos. Across the country in Atlanta, Soulja Boy offered a similar critique through his digital native dance rap, celebrating social mobility through entrepreneurship in the emerging digital landscape. The mainstream co-opted and made a spectacle of Soulja Boy’s dance rap. Today, as Soulja Boy’s one-man credit reclamation campaign rages on, rap media pundits and professional haters alike must concede to his contributions as an originator of modern rap, marketed online.

“Watching people literally turn on the camera just to step back and…dance in front of it wasn’t happening before Soulja Boy,” Juju says.“It definitely wasn’t happening out West, with real dance moves, really tryna show your skills until Jerkin really hit the scene.”

The reject

While Jerkin prospected and generated the demand for a more meta style of hip-hop, acts like Lil B, Das Racist and Odd Future would ultimately meet that demand as the blog era calcified and streamlined its culture commodification agenda. For a while, jerking fell out of favor. Forgive casuals who see jerking as a relic of a bygone era, with its influence largely confined to pop culture nostalgia. But it came back as no surprise to those paying attention.

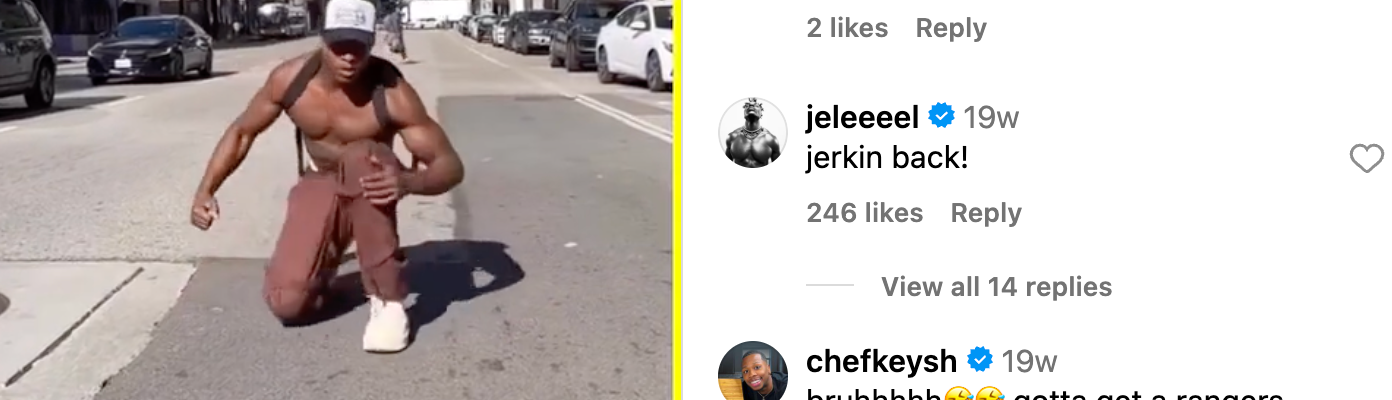

In 2021, a TikTok tutorial teaching the jerk dance garnered over one million likes. Jeleel, the hyper-viral artist of backflip notoriety, released a nu-jerk song called “Gnarly,” vowing to "bring Jerkin back." These are not isolated incidents, but rather a reflection of the dynamic nature of Black cultural remixing.

The return of Jerkin is more than just a retrending dance fad; it's a critique on the state of hip-hop today. Current hip-hop has embraced an unprecedented level of negativity, with the debate on who bears reproach still raging in classic chicken and egg fashion. On the whole, future modern tends to pin the blame on some mix of out-of-touch major record labels, corrupt rap media voices, and inattentive music consumers stifling hip-hop’s potential to stoke social revolution and ultimately threaten the ruling powers (who, of course, architected this pro.

Failed public policy also shares significant blame here. Government's role in the modern expropriation of the Black voice in hip-hop traces back at least to the Telecommunications Act in 1996, which, on behalf of the majors, ensured the overtaking and gutting of Black radio and media by white-owned labels. Yvonne Bynoe writes about this consequential legislation in her essay, “Money, Power, and Respect: A Critique of the Business of Rap Music,” six years after the act passed:

"The Telecommunications Act of 1996 facilitated the control of radio by a few conglomerates. This legislation allowed one radio company to increase its ownership to eight stations in a given market, thereby squeezing out many independent radio station owners. For example, in 1998 New York City had twenty-three FM stations, and three companies—Chancellor Broadcasting, CBS, and Emmis Broadcasting controlled eleven of them. Moreover, the Telecommunications Act abetted the loss of 39 Black-owned stations nationwide."

We could write another long-form story drawing the straight line from the War on Drugs, to prohibition begetting violent crime, to the incipience of mafioso and gangster rap subgenres. For the most recent policy assaults on hip-hop's social potential, look no further than Covid-19. Black people faced an onslaught, from their stereotyping as more prone to infect others, to the killing of George Floyd and the subsequent co-opting of the grassroots insurrectional response by celebrities and NGO complexes. The failure of those in power to responsibly contain the spread of the virus induced even starker and more extreme wealth inequality, coinciding with the U.S.’s largest year-over-year murder rate spike since at least 1905, and the hockey stick moment for drill as the fastest growing music movement in the world.

It’s deeper than “music misguiding the youth” complaints in an “old man yells at cloud” gif. The behavior permitted by music literally supplants the lived existence of teens who inadvertently fuel a machine built to destroy them. The youth watch passively through the screen a procession of images realizing a separate, unreal reality preemptively decided for them in a realm of production they have no power to interact with. And now it goes beyond compelling the youth to merely identify with the destructive behavior; they must repeat and reproduce the behavior, their validity only extant to the extent they embody the meme.

As these ruling powers concentrate, the chasm widens between the people and the voices representing them. When we had five major labels, the hardest rappers rapped about selling drugs, not doing them. Lyrics about shootings generally targeted vague, unnamed enemies. Implicit to these street tales was the sense of outgrowth. Past tense violence. Recent years have seen the industry subsume BMG and EMI to form the three major labels we all know: Universal, Warner, and Sony. They themselves are holdings of larger multinational conglomerates selling everything from news media to oil to houses. Chemical conglomerate Access Industries CEO Len Blavatnik controls over 99% voting power in WMG, while holdings and logistics company Bolloré, owns 18% of UMG, and additional holdings via their stake in mass media corporation Vivendi. So much of the music we love, for better or worse, reinforces rule by the wealthy at our expense.

While that dynamic isn’t new, it provides context for our cultural position today. Unless a song states the exact address and government name of an artist’s murder victim, paired with a video choreographing a dance that pantomimes the murder, as “Notti Bop” infamously did, does it go hard enough? These songs hit different when you remember that financial holding companies such as BlackRock and Vanguard have ownership stakes in both major labels and private prisons. While some hip-hop fans view the prison-label connection as contested mythology, we remain convinced that these dots are worth connecting. The “secret record label meeting that destroyed conscious hip-hop” didn’t need to actually happen because it happens everyday: artists, from Lupe Fiasco to Too Short, have encountered resistance from their labels when trying to share more positive music. This context makes Jerkin start to feel enlightened by comparison.

Wobbling kingdoms

Earlier this year, Lil Durk released “All My Life” featuring J Cole. A distinct departure from his usual output, the song sees Durk pleading with the youth not to do drugs between a children’s choir hook. The track immediately throttled to #1 on YouTube Trending Music, out-streaming NBA YoungBoy’s entire new album in their first week. For his part, YoungBoy has recently made media waves for renouncing his previous gangster lifestyle-based lyrics, opening up about his journey to grow as a role model.

Suddenly it seems like even the innermost circles of mainstream music have picked up and begun to internalize the signals we and many other culture commentators have emitted to the industry. Even Complex is wondering aloud whether drill’s falling off. But the question remains whether these insiders have genuinely begun to correct their course, or simply work harder to conceal a nefarious plot. Ice Spice is positioned as the model of positive — or at least not overtly violent — drill music, the hyperrealistic gangsta rap genre popularized by artists like Durk. We know she has the same handler (Elliot Grainge, son of Lucian Grainge) as 6ix9ine. She appears to follow brand friendliness as a guiding principle more than any particular message, but she can rap, brings a great vibe, and let's face it, we all love her. So how should we approach this? Probably just as it is. Objectively, we don't know where she's taking us yet, and I believe she has some artistic potential, but I think we should be wary of how industry tactics will modernize in this era of signaling virtue, rather than practicing it.

We predict that as the music climate continues to change, Jerkin will remain relevant, with another viral moment always just a 2-3 step away.

This story was published through Liner Notes' editorial program, submitted and written by chibu ichiban of future modern. To learn more about our program and pitch a story, read our guidelines here.