We’ve all got inanimates we treasure.

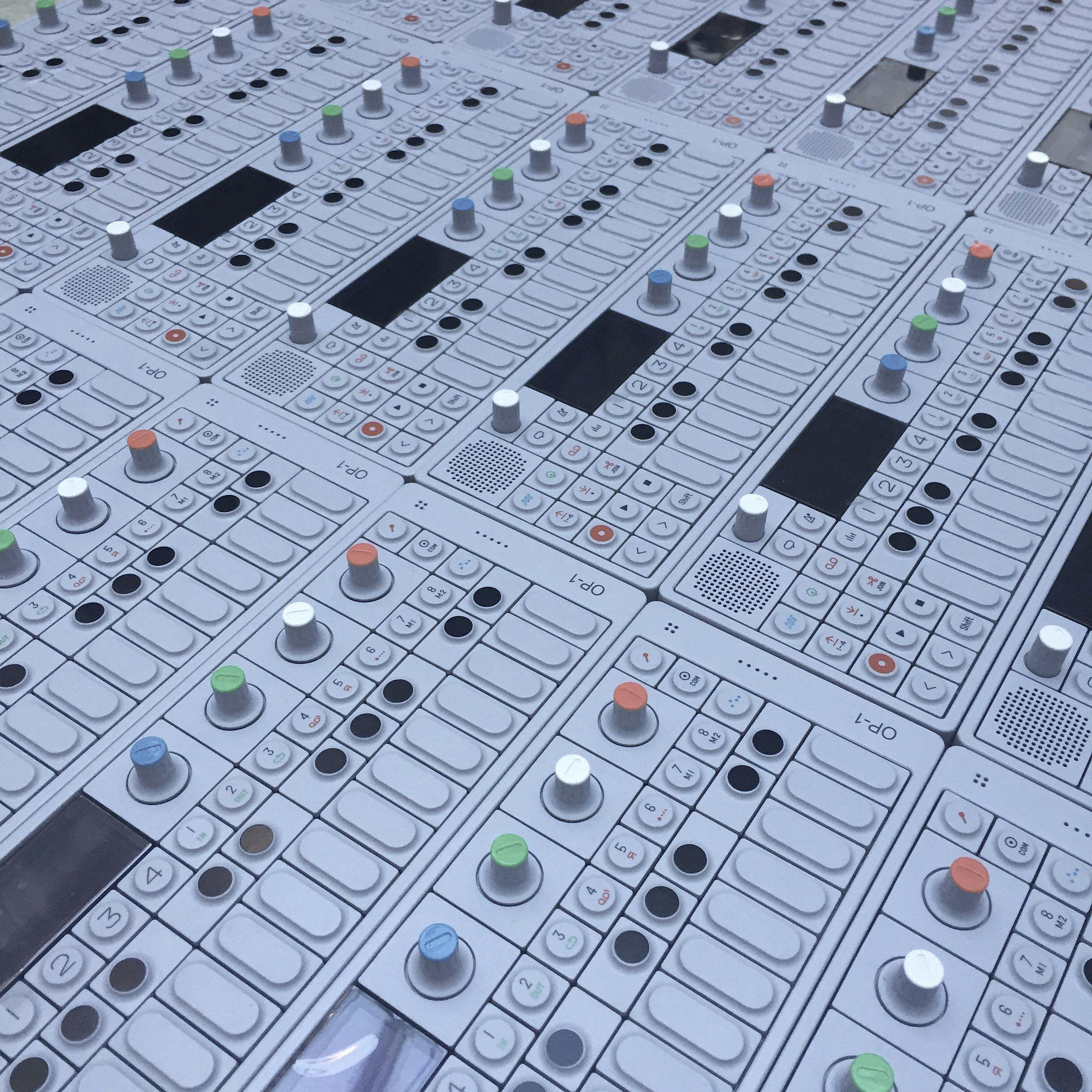

007 and Q’s loot. Static Shock with the saucer. Kim Possible’s Kimmunicator. Let’s throw Squidward’s clarinet into the ring too (if his pineapple-dwelling neighbor keeps quiet). As for you? Odds are, you own (or want) at least one piece of hardware from Swedish juggernaut Teenage Engineering, the crew behind the OP-1 synthesizer and a decade-long run of other products that beg to be toyed with.

They’ve become shorthand for industrial design excellence in the tradition of Dieter Rams (subtle, compact, matte, functional) with a creative spark that honors its leadership’s audio-obsessive origins and its team’s deep roots in gamer nation. Whereas most Apple products strive to vanish within their elegance, TE devices often dare you to play: a welcoming, approachable aura best illustrated by the Pocket Operators that have entertained so many of us for years. Appreciators of opinionated design can bask in the idiosyncratic glow of the Playdate’s crank, the OP-1s cow stomach effect, the TP-7’s seesaw toggle.

TE, like any company, isn’t faultless. Temptations to adorn for-profit entities with saintly halos are worth resisting. (Spend a few minutes digging through your synth forum of choice and you’re bound to uncover a heated debate about the org’s price and purpose.) Nonetheless, TE’s commitment to obliterating the bare minimum (a bar few consumer electronics makers bother rising above) remains commendable, and consistent.

I’m of the belief that this run, rare in that it prioritizes craft and patience over Logan Roy ruthlessness, offers lessons for all of us working in and around the arts. TE has proven itself capable of finding harmony between creative judgment and self-sustaining business decisions to nurture a discography of their own; their pride is prerequisite for commercial release. As a result, its product practices have a strong chance of translating to the people using their tools to create art.

In pursuit of secrets and spells, we spoke with Teenage Engineering co-founder David Möllerstedt about a hell of a lot: design principles, the late A$AP Yams, remixing yourself, specialization, etc. We hope you enjoy the conversation as much as we did. Keep going and stay safe out there.

Do you use Teenage Engineering tools as instruments for your own music?

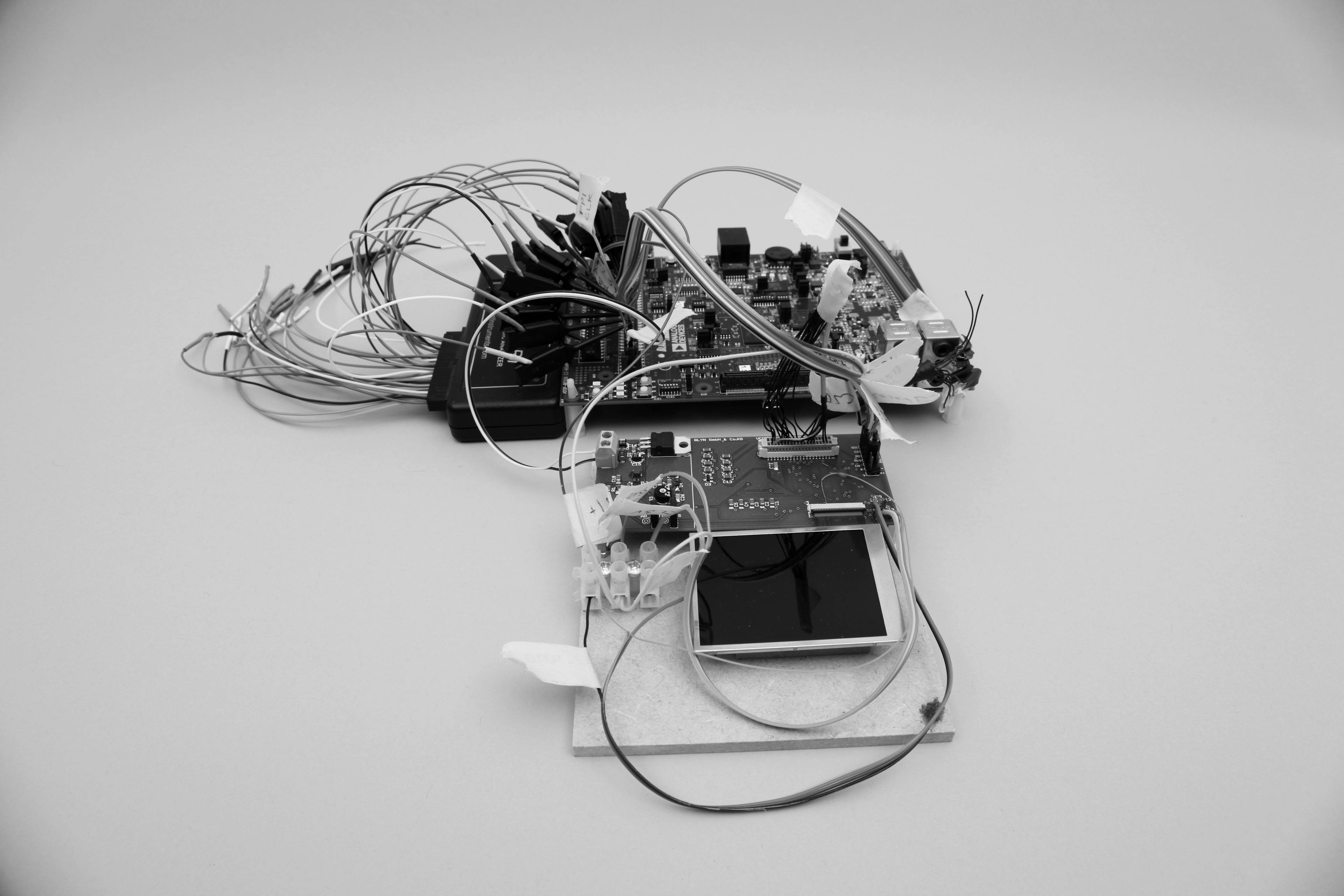

Years ago, we started a band called Teenage Engineering Sound System to make sure we were testing our products and prototypes live, in front of people. From a studio perspective, our team had lots of experience, but less so with performing. The band was a mix of engineers here who made music and artists we knew well. We played in Stockholm, at festivals in America and Denmark, and in Seoul. We’re restarting that practice now. We’ve got a special Jeep we’ve been using to test the field system. We might sell it at our garage sale in Stockholm [Laughs].

Imagining a TESS comeback tour kicked off deep in the Nordic forests. During the music-making process, we might hear 30 versions of a song 300 times between conception and ‘completion,’ to the point where silence is better than hearing it again [Laughs] Familiarity can dull whatever magic once lived in the record, and a lot of music never escapes the Notes app or the private SoundCloud for that reason. When you release a product, do you feel a need to separate?

For synthesizer projects I’m a part of, like the OP-1, it actually does become tricky to use it creatively. You start to only think of it as a technical tool. To lose that, it requires taking space, but I’ve been able to eventually come back to them. It’s easier to switch from developer to user with our speakers. I use the OB-4 speaker every day to listen to radio. That’s taken over from the OD-11 for me. But it’s really nice to get products to the public and see the reaction. That’s what we live for.

If the outside world doesn’t respond well, do you adjust?

We do need to acknowledge that if we didn’t, we’d act as a conceptual artist, not a company, which is different. For the most part, the product concepts that went wrong are products you haven’t seen [Laughs]. We’ve been lucky to have enough things that people wanted to pay for. That’s another difference. Someone can like a thing, but will they buy it? It means a lot to put your hard-earned cash into a tool, and hopefully get something in the mail later.

Hopefully! [Laughs]

In the early days, there was a level of trust in us as an unknown, small Swedish company that was mostly sending stuff to the U.S., where people were buying the early OP-1s.

Those were your day ones.

We really used to sell everything directly. They had our email addresses [Laughs]. There wasn’t anyone else to talk to but us. We received lots of feedback and met lots of people. We still talk to some of them.

When is it time to kill your darlings?

It happens later than it should! But we often don’t kill something. We just say, “Let’s put this on pause,” which is an important distinction. It might just not be the time for something, but it can become the right time. There’s always a connection between products. The OB-4 was in a prototype stage for a long while before we felt it was right to release it. The tape wheel you see today in that product initially started as a kind of lever design, which inspired the crank in the Playdate device we co-created with Panic. And that tape wheel we landed on for the OB-4 is now the centerpiece of the new TP-7, just larger.

Testing and learning about different things that work allow us to move them into other ideas down the line. Within the walls here, because we only have about 60 people, we can all connect those dots from memory. There’s no massive Figma archive people can hack and steal [Laughs]. Ultimately, though, finishing things is essential. Anyone can imagine a product and it’s fantastic. You can always dream about how wonderful something will be if you only release it in a parallel universe.

Do you see the TE desk as an experimental release? That’s one of the few products I’ve seen released from Teenage Engineering in awhile that caused noticeable confusion.

That confusion may have been a result of how we presented it. We see the desk similar to how we see the TX-6 mixer, which doubles as a 12-channel audio interface: it’s a complete system. And the desk is modular, just one thing you can build with that structure. Our kitchen is made of those same parts. The chair I’m sitting on is made of the desk components. The beauty of the aluminum rods is the ease of cutting them at any length you want. But we decided on presenting it as a desk first because that was the simplest, and most relatable, use of that system. That was the path to product-ifying it.

In a way, the CM-15 mic also felt like an experiment. It was a mental obstacle to make it in the first place, because I wasn’t sure what the perception would be of Teenage Engineering releasing a microphone. We had to learn how to do a mic from scratch. We knew what we wanted, design-wise. We knew what we wanted, quality-wise. But how to get there? [Laughs] We just had to learn. The CM-15 and the TP-7 both contain mics, but the internal systems are so distinct, so we didn’t save much time or effort there either.

We just published a story about the battle against non-effort in music, characterized by Frank Ocean’s divisive Coachella performance and ChatGPT, with the artist Danny Dwyer. In that story, he described electricity as a sort of magic he wanted to understand. Mics feel that way to me.

I come from a recording background and I like microphones a lot. It’s funny because a mic is really just about taking audio and making it a waveform. It’s simplistic, an air-to-electricity interface. You don’t want a mic to be too weird because you’ll apply effects later. Your voice is so personal; it’s the most human sound there is. We can immediately feel when something’s wrong with a voice because we’ve been trained since we were born to do that. That makes mics delicate instruments… It has to be true. And the input/outputs need to be super clean. That way it can work with high-end gear in the studio, or directly with a computer. Accounting for both scenarios in a form factor that’s meant to be the size of a deck of cards was a challenge. It’s not a lot of space to fit what you need to have to do that conversion.

Did you start with the form factor as the leading constraint?

We did start off with that deck of cards as our packaging reference, which also applied to the TX-6 and TP-7. From there, for the CM-15, we figured out how we could best fit a one-sided mic capsule inside, and we made the judgment that a cardioid mic would be most useful for most people. Then the challenge becomes fitting in all the electronic components you need while ensuring there’s no interference or unwanted noise leaking in, especially when you have a combined digital-analogue system. When you do a mixed system with that little space, it’s tricky. The decision to go with a mini XLR, covering the pro audio side of things in a nice way, really helped us pull it off. Part of the CM-15’s reason for being is its compactness.

“Compactness” feels like a unifier for TE products, even though many are larger than the field system series. There’s rarely a sense of wasted space. At the same time, they live with their own identities. The new TP-7 has that striking synthetic leather back panel in orange.

Every product has its own color palette. You’ll see that yellow is nowhere near the OP-1, but the OP-1 field has a mustard yellow, golden knob; the OP-Z has a yellow dial; and the 400 comes in a yellow encasing. The OP-Z exterior has that marble texture from the material we use in the injection molding, whereas the OP-1 field has its aluminum body. Both have variations of gray bringing them together. Lowercase lettering is appealing because it’s more democratic. I write emails like that now.

I can’t lie: every time someone messages without caps, I feel a spiritual alignment [Laughs]

Numbers are never capitalized or lowercase for a reason. Every letter should have the same weight. That’s what we adhere to with our guides and website, down to the section headers and calls to action:: “add to cart,” not “Add to cart.” But abbreviations should be capitalized: MIDI, OP-1, etc. Because that represents something longer.

Lowercase still feels like a secret handshake at times, even if enough people roll their eyes at the behavior. A lot of it’s just internet culture, Tumblr talk, that ebbs and flows in popularity. Olivia Rodrigo having an uppercase album title (“SOUR”) and lowercase song titles in 2021 led to think pieces. In some circles, the immortal A$AP Yams gets the credit. In your case, do you think Sweden’s political history plays a role in the allure of minimizing big letters?

We had a mixed economy, which meant a strong state and a strong corporate world. We were sitting between the Soviet Union and the west, existing apart from NATO. Many Nordic countries have stronger welfare states, so in that way, democratization connects as an influence.

The magic of TE might be that design achieves a uniformity while remaining playful, whereas uniformity in other contexts may feel boring, or lifeless, which is where you get the intentionally incoherent, chaotic graphic design rising up in rebellion. Both can yield special results.

I think that’s true. Having a uniform base allows you to have exploration beyond it. Or else you risk being messy, if you don’t know your own foundation. Simplicity and uniformity are also distinct from blandness.

The subtlety of the OP-1’s form makes the onscreen visuals, like the cow effect, even more memorable.

And even that is consistent with the action you take as the user. Our synth screens are more scientific, while our effect screens are more exploratory. The cow effect was created by Magnus Lindstrom, who’s famous for Microtonic. He described what was actually happening to the sound, Jesper sent me some Illustrator files, I coded them, and we referred to it as “ko,” or cow in Swedish.

That effect sounds like it’s getting processed in multiple stages. Weird stuff happens in each one before it comes out the other end [Laughs] Pairing sound with a visual and vice versa is a big part of what we do. It doesn’t always work. Once we had a visual animation inspired by impossible geometric figures. It looked so intriguing, but we paired it with an audio effect that just didn’t complement. It didn’t sound like it looked.

Visual indicators weren’t responding to, or representing, the sound naturally.

Exactly. They have to live in the same world. The visual is meant to be a helpful abstraction, instead of having a filter capped off at 287%, but it still has to communicate clearly, even if it’s creative. I think it’s nice to not need to look at numbers when you’re making music sometimes. It can be frustrating to have to figure out if you should set something to 500 or 498. These abstractions force you to listen in a different way. It feels more musical to me.

There’s a forever debate, or cultural negotiation, about the borders between artistry, craftsmanship, and entertainment. Where one bleeds into the other, whether it matters, and why. TE is a for-profit product company in the traditional sense, which creates different audience expectations than an ‘artist’ might have, but more and more artists think of themselves as a for-profit product company, for better and for worse, and TE challenges social pressures to grow.

I think there is artistry in toolmaking, but that kind of artistry differs from performing. We’ll try out new technical ideas early, but we don’t put our bodies on stage to the same degree. The work we do might be passionate, but the end result isn’t a person. It’s more abstract. It’s super tricky for an artist to cover all bases. You’re just yourself, or if you’re a band, you’re a couple people. And it’s hard to make music, organize a tour, and sell t-shirts, or hand it all over to a record label that gets it wrong. You want different angles on whatever you’re doing, but it’s hard to find that. That’s the power of having an umbrella like Teenage Engineering, where people from different domains can come together toward a shared goal, and do almost everything in-house. You want people who do different things, like what they do, do it well, and want to collaborate. Otherwise you risk losing control of your own destiny.

Your products do feel personal, or at least opinionated. Even when TE catches flack at times for its prices, there is almost always a wave of praise: “Only they could have pulled that off.” It’s even become popular for designers to try and remake existing products from other organizations, like Apple’s AirPods, in the vein of TE, even if Dieter Rams’ influence exists in both. That’s rare. Scale economics have continued to sand down most idiosyncratic design and risk.

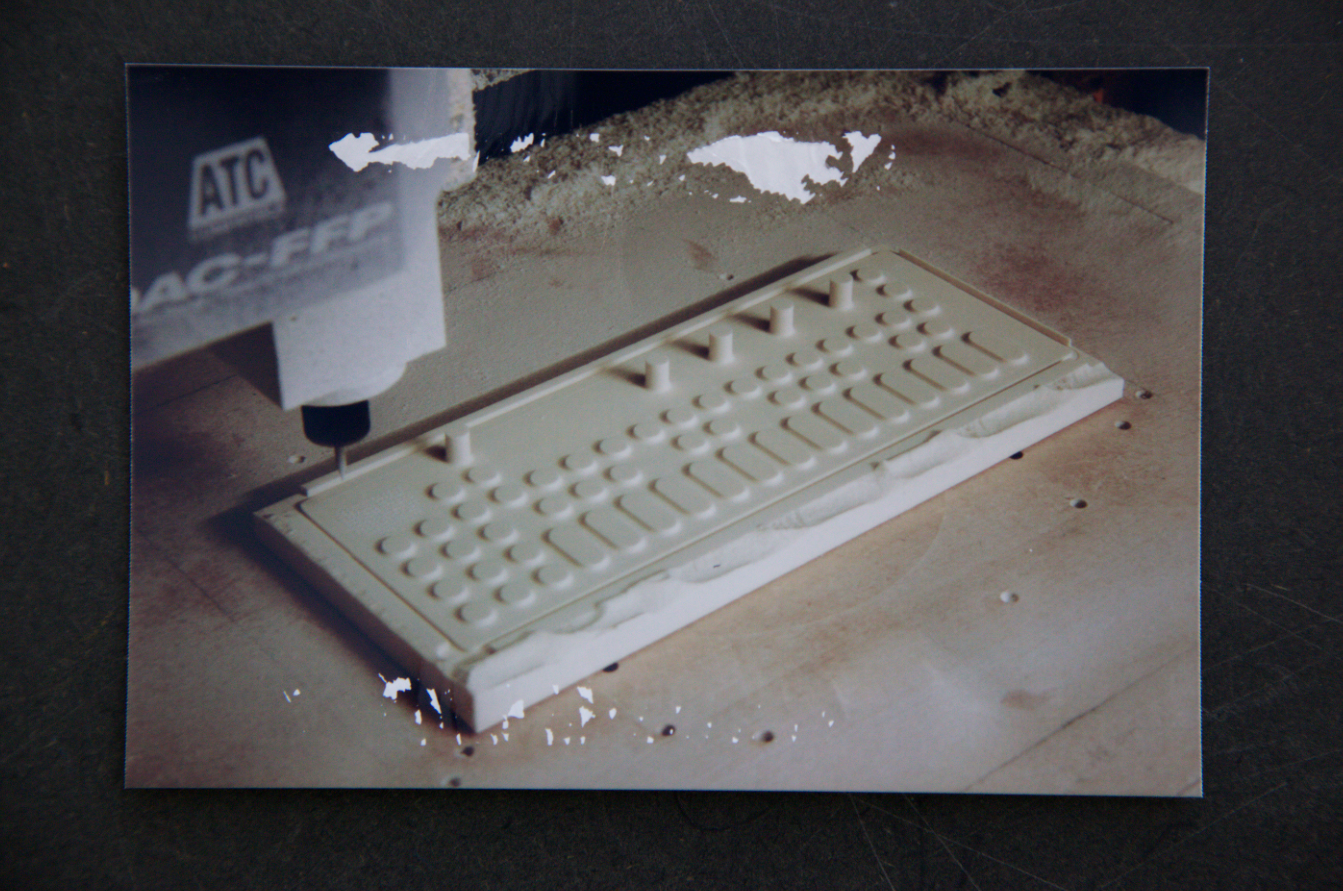

I think about how something becomes a product. We do a lot of prototypes with physical objects. But somewhere along the line, it has to evolve. You start with this huge field of stuff. But the product requires more restriction and concentration. It’s like you drop it into a funnel. You have a concept and guidelines. The constraints will tell you whether you really have something. For us, and for users, constraints are usually helpful. We’re doing something that isn’t as open as a computer. On a computer, you can have any number of files or programs. It’s almost infinite possibility. That can be fantastic but also tricky.

Blank page syndrome.

Yes. We try to narrow things a bit. We think of our products as single-purpose objects. We’re providing a box. If it works for you, great. If it doesn’t, you can realize that quickly and move on. This also makes it easier for us to improve. We’re doing software and hardware. Both disciplines are limited by finance, manufacturing, and our own judgments. The interesting stuff happens when the device reaches the user and they push those boundaries in ways we didn’t think of. I know our tools inside out, but that creates a limitation on myself. The true creative test is when someone else tries to break it, and the device supports that ingenuity.

How does price affect a product, in your experience? At what stage does it become a constraint?

When we get to the end, price usually isn’t something we can tweak. Production, printing manuals, shipping, and certifications contribute, as does the sum of the parts within the product. Early on, we have an idea of where we want to end up. Sometimes we hit that mark, sometimes we don’t. The Pocket Operator started off with the price as part of the concept. We wanted it to be $49, and reuse as much existing code as possible to shorten the production schedule. We made the casing an optional add-on. Some people built their own. I think it ended up being $59 at launch, which is pretty close, and now the entry price is back at $49. We did the first one with a jeans company. They wanted something that could fit into a jean pocket and have a similar price to a pair of pants. That was the fundamental constraint.

Recycling ideas at the expense of new ones ≠ remixing yourself.

The OP-1 field, which we released last year, over a decade after the OP-1, still let us reuse quite a bit. The first step was to adjust the hardware. USB-C, upgraded Blackfin chip, all of that. Once that was in place, we were able to port the code from the original OP-1, patch things up, and add new features. The manufacturing of the field also happened in the same place as the original, which was a massive benefit for us. We try to produce things with a higher finish, or perceived quality, than what you’d normally get at the production volume we do. It’s really only the biggest names that can match or exceed that. All of this starts with a small team. It may have taken one or two people from mechanical engineering, and two or three from software, to make the OP-1 field a reality and lead that project. A lot of us help push something over the line, because we do our own product images, instruction manuals, websites, and presets.

Regarding the process at TE...

...products are more fun than process [Laughs]

[Laughs] That in-house commitment across mediums yields these details, which, on the receiving end, translate to proof of care. I think that’s a big part of what “world building” boils down to. It’s a weathered, maybe overused phrase. Still, it remains an existential mission for so many of us, even if the motives behind that ambition vary wildly, or at least reflect economic pragmatism as much as creative spirit. But TE does achieve some version of that goal, down to the pixelated characters in the Pocket Operators. I heard Jesper tried to make himself less involved to empower others.

Jesper is my boss, so if he said it, I agree [Laughs] If a group can form internally around a concept and they are capable of executing, across disciplines, it has a chance. If you have an idea, you need to be able to work on it, and if you can do that, you have a lot of say.

What organizational bad habits do you avoid to safeguard this?

Many of us here have worked elsewhere, in gaming, with huge teams, and that’s taught us a lot. It’s about getting the most out of hardware to feel intuitive and snappy. We try to avoid regular meetings with no purpose as much as possible. We have one mandatory weekly morning meeting at 9am and we try to keep it to 15 minutes maximum. Then each product group may have a weekly meeting, too. We don’t have a lot of people who need to go around and ask a lot of questions, like, “how’s it going?” to put a number in a spreadsheet. You need to be very technically skilled and conceptually understand product development. It’d be difficult to do what we do if you had one person tasked with the design and no technical knowledge, and someone else just waiting for a piece of paper with specs. The feedback loop is way too long. If you can use yourself as a yardstick for what you’re doing, you can test instantly, all the time. We try to let people do stuff and hope people do the right stuff. That admittedly puts more pressure on the people here, and it’s led to us growing quite slowly, but it’s also a nice structure to keep.

Once a month, someone on the timeline wonders aloud why a tech giant hasn’t bought TE. Is it safe to say that slow growth still reflects the intent of your team?

Well, in terms of growing the number of people we have, if we could find great people who wanted to work here, we would happily hire as many as we could fit [Laughs]. But there’s a limited set of people who have the skillset, and want to live in Stockholm, Sweden, and have the interest. In terms of growing the company, I think we want to have our stuff in as many hands as possible. There’s no breaks on that. Especially when you think about the Pocket Operator and its lower cost, which has made us more accessible. We never wanted to be elitist, out-of-reach expensive.

The way you talk about growth, “no breaks,” is similar to a lot of artists, in the sense that we want to be heard as widely as possible. I’m of the belief that there’s a rare power in the artists who have some form of that ambition, but refuse to let it lead them too far into cookie cutter territory. Those artists push pop culture. How do you preserve your ingenuity while aiming high?

When I say I want to get into the hands of as many people as possible, it’s still with our product. If we had to compromise that, it would mean nothing. We feel that if we create something we’re proud of, we feel happy the more people also like it. If we do something that very few like, but we’re happy with it, we’ll still do it. But ideally, we want lots of people to appreciate what we do. But I say no a lot. I don’t like to say no, but we need to be able to justify why we do something

Would you say you’re on the trusting end or the protective end of the user research spectrum?

I think we’re definitely on the self-trusting side, but maybe not so much on the protective side. It’s interesting to get input all along the product development process, we might just ignore some of it. If you ask people what they want, they often won’t know what they want, especially if it’s a bit new. It’s also very difficult to explain a concept to someone. That takes a long time. They need to really understand what it is to give meaningful feedback. You need something half-baked, at least, or else they might say, “Hey, this part doesn’t work!” Well, yes, we know [Laughs]. The most valuable thing we’ve done, and want to do more, is grow the team with people who have different backgrounds of expertise and offer different input. The product inherently has more possibility of being widely adopted, because it reflects more of the world.