“Is anyone listening out there?”

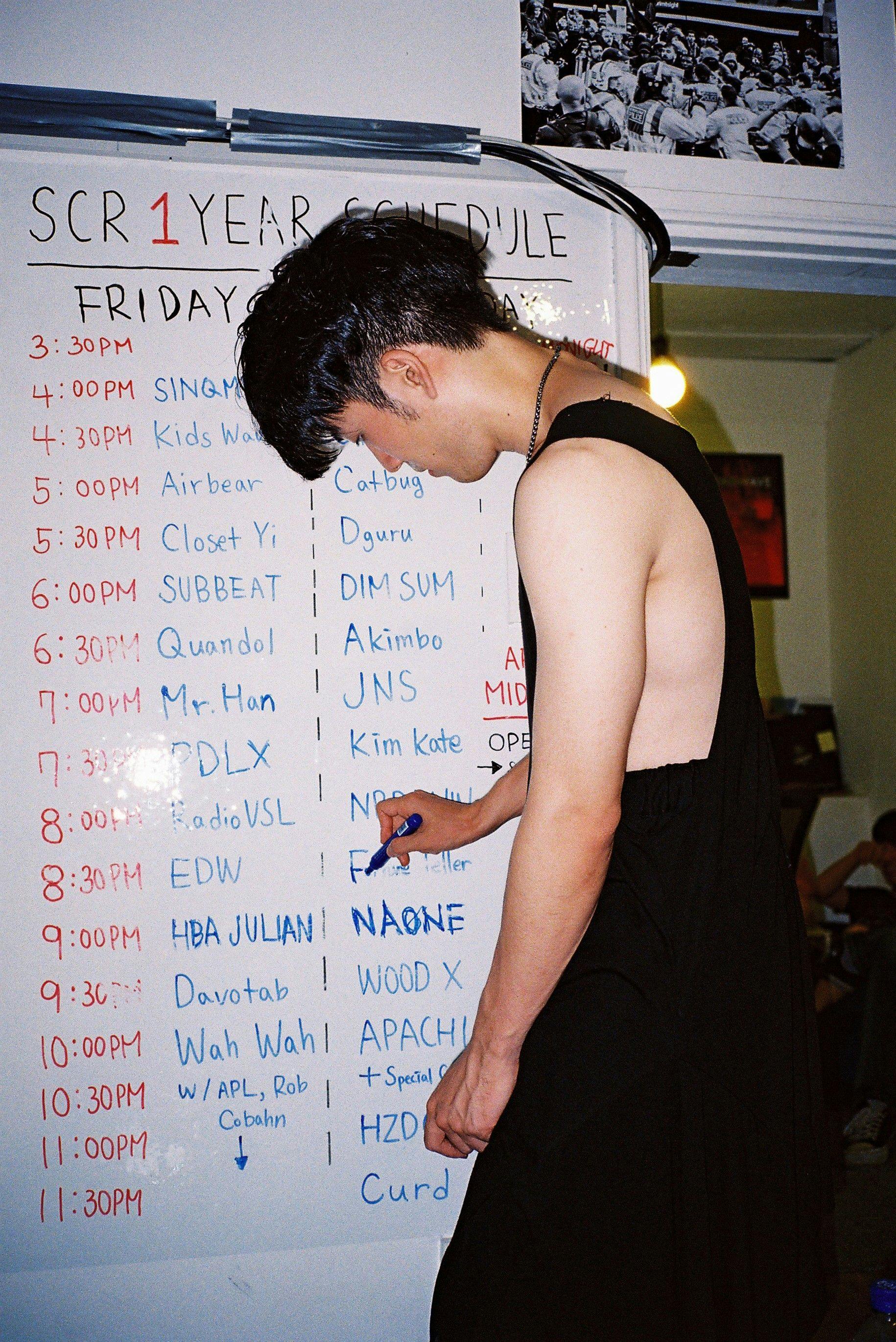

On weekend nights in Itaewon, Seoul, crowds of techno and jungle lovers congregate at Seoul Community Radio, bodies spilling into the street. Inside, local DJs command the decks in front of a green screen, where digitized graphics will soon appear for the enjoyment of online viewers all over the world. Gleeful audience members bounce in and out of view for those tuning in. Since 2016, this broadcast station has become a fixture in the underground music scene of South Korea’s capital, creating a living archive of the diverse homegrown talent that’s exploded over the past decade. Radio waves are ephemeral, but the file (and friendships) are forever.

“There’s no night that’s the same on SCR,” says co-founder Richard Price, who DJs as Vinyl Richie. “We try to put forward people who are innovative. We want to keep it underground. We like to have people and collectives with ideas hit us up.” He cites a local DJ collective called KIRAKIRA, who highlights anime sounds and aesthetics, as an example of the kind of envelope-pushing talent they get excited about.

The rise of SCR goes hand-in-hand with the emergence of Seoul as an electronic music destination, with the station connecting the local scene and a global dance music network. Throughout the years, SCR has broadcasted sets from big names like Yaeji, Peggy Gou, and RP Boo alongside local heroes like FRNK, Kirara, and Salamanda. Their antenna is far reaching: They’ve welcomed punk musicians from Los Angeles, Afrobeat collabs with South African crews, and link-ups with local stations in Ho Chi Minh and Bangkok.

At the same time, SCR has become a community hub known for hosting DJing and Ableton workshops, collaborating with local restaurants to fundraise for causes, and throwing the most creative parties, from jjimjilbang sauna raves to barbecue restaurant takeovers, that have converted everyday Koreans into club-goers. Price and his co-founders Seulki Lee and Juhwan You (also known as DJ Bowlcut) have run this independent hub for almost eight years, even surviving COVID. With no government grants to lean back on, they’ve had to fight the older generation’s preconceptions that clubbing is unsavory. And in true Seoul fashion, they always feel the pressure to come up with the next great party idea, the next standout collab.

“Everything with SCR has been hand-built,” Price says. “[We’ve] had to bootstrap the whole thing and run it like a family business.”

SCR’s “think globally, act locally” attitude stems from its 2016 origins, when Seoul’s electronic music scene was beginning to boom. According to Price, there were only two clubs back then: the now-defunct Mystik and Cake Shop, which garnered attention due to the attendance of celebrities like BigBang’s G-Dragon.

“People from far and wide [started deeming] Korea an essential pitstop on their tour,” Price recalls.

Seoul-based DJ Seesea, who also goes by DJ yesyes and Techno Gaksuli, remembers the mid-2010s for how outsiders injected inspiration into the scene: overseas artists regularly toured Seoul clubs and made local DJs feel like they could build careers of their own.

“By watching these foreign artists play, I could observe mixing-related methods and skills,” she says, explaining that Koreans also learned of international acts through Rinse FM. “I think it helped spark fresh curiosity in audience members and maintain their interest in these new sounds.”

In the swirl of this growing hype, Richard Price, a British national of half-Thai ancestry who had recently moved to Seoul, caught a spark of his own. Inspired by the pirate radio stations he grew up listening to in London, Price brought the idea of a like-minded Korean platform to his friends, Lee and DJ Bowlcut. The three decided to call their endeavor Seoul Community Radio and began uploading scrappy sets on SoundCloud.

“Back then, we just wanted to show people what’s cool,” Price says.

One of those early sets featured Seesea and her all-female crew Bichinda, which she founded in 2015 due to a lack of parties that spotlight women DJs. Seesea still frequently spins for SCR, which has since uploaded more than 3,000 sets on YouTube.

“It’s a place where people can freely make social connections because everyone is welcome regardless of musical value, taste, gender, origin,” Seesea reflects. “Also, because fellow [SCR] members have set down roots [through the platform], it feels like my family.”

Their chosen location of Itaewon, known for its mixed population, also reflects the SCR ethos.

“That’s where there’s the intermingling of international cultures,” Price says of the neighborhood. Sadly it's getting demolished and made into luxury housing. In its heyday bike shops and tattoo parlours would mix with LGBT clubs and the city’s main mosque all on one road. Now SCR is about to turn 10 and it’s all at risk.”

Formerly home to a U.S. military base that led to the area’s liberalization (its Western influence immortalized in the 2011 song “Itaewon Freedom” by UV and JYP), the district has since morphed into a nightlife destination and hub for expats and tourists. Walking down the neighborhood’s colorfully lit streets at night, you might hear U.S. hip-hop blasting from the speakers of a restaurant, or see an Irish bar sandwiched between a Moroccan eatery and a Russian cafe.

SCR’s rising profile echoes the climb of Korean culture to earthwide zeitgeist, with hallyu now on equal ground with Hollywood.

The question of globalization’s influence on South Korea is not so cut-and-dry. U.S. military presence continues to mount alongside blockbuster-inspiring inequities in major cities, much like other metropolises around the world. And yet to many young Seoullites, there’s indisputable benefits: Who wouldn’t want their favorite musician to finally stop by their town, or at least appreciate troves of people halfway across the planet learning your language on Duolingo? Many creatives also see isolationist xenophobia as relics of their parents’ generation.

SCR is a confluence of all these rapidly shifting changes and attitudes in the country; because the platform welcomes outsiders, they’ve become an entry point to Seoul’s broader music community for people like James Gui, the writer and DJ who spins under DJ Hot Pot. After moving Seoul from America in 2021, Gui found it easy to make friends at SCR events and play gigs there, even though he didn’t speak much Korean.

“Especially during the pandemic when no one else was going, the fact that I was moving in, they were like, ‘Oh cool, something different,’” Gui says. He sees SCR as a stepping stone to discover parties and collectives who promote in Korean to a local audience, like ACS.

Price, like Seesea, believes that international attention has helped “add weight” to Seoul’s scene and inspire local musicians. Now, there’s many South Korean artists in demand to play gigs abroad, with more opportunities to DJ and perform across Asia and the Global South than ever before. “Now places [like Karachi, Manila, Shanghai, and Singapore] are developing their own scenes. Dance music has become way more global in general.”

Calling from his mother’s house in Bangkok, Price talked about the station’s beginnings and pitfalls they encountered along the way, while testing out potential party concepts with me (including an idea to tour different Koreatowns across the world). See our edited conversation below.

What was your mentality in starting SCR? What were those beginnings like?

In 2016, Korea was starting to get on the map, culturally, for different artists, promoters, and people doing creative stuff. So with SCR, we began to record stuff and put it on SoundCloud. We had a working title, Seoul Community Radio, because there was Berlin Community Radio at the time. We just kept it, because it’s so perfect: It just says what we are.

After doing the SoundCloud thing for a year, we decided to go all in and make a studio. We rented a really small basement. I think it was $400 a month, and even that was a bit tight. It was BYOB, and we wanted to be nice to the DJs, so we'd always go to pyeonijum [convenience store] and buy drinks and stuff. We’d have the odd big-name artist playing in this bunker, and people would be trying to storm it. It was like a house party vibe. After doing that for three-and-a-half years, we decided to get a second place that had its own mini bar, and we could have more seating. We wanted it to be more inclusive and help people learn more about radio, the music scene.

Now I feel like SCR is a [stepping stone] for DJs in Korea, in the same way it is to get a set on Rinse FM or NTS. It's sort of a badge that says, “I’m a credible DJ,” or “I’ve got something worthwhile that the radio wanted to put on.” Now we have established DJs bringing through the next generation, because in [Korean] society, they have sort of a [sunbae (mentor)] and [hoobae (mentee)] kind of thing. DJs have their cycles; they train the younger ones, and then they bring them through, which is an incredible thing to see.

What are your early memories of music discovery through radio?

I’m in my [late] 30s, so I still remember actual radios that come with a stereo, and I used to play with it a lot. More often than not, there would be these sick London pirate radio stations playing these tunes that an 11-year-old London kid would like. They’d be playing this amazing music that I’ve never heard before. It just made me want to discover more.

I even used to text into the pirate radio station. There was one near me called Point Blank and another very famous one, Rinse FM, which turned into what it is now. There was Kiss 100, which is a London-based channel that also became commercial. There was a big boom of these pirate radio stations getting commercial licenses, which some people said changed the mentality of it all and that was the controversy of the time. BBC Radio 1 also onboarded a few of the more well-off pirate radio DJs. Without those moves, you wouldn’t see the big UK artists of now, your Skeptas, people from the world of drum ‘n’ bass. People would tune into the pirates to get it, so it forced the BBC and other commercial agencies to get on board with that spirit.

One of my favorite things of that era was teletext. It was pre-internet. It was a very pixelated information screen. The radios would put their tracklists on teletext. You could buy a page from the TV stations, so the pirate radio stations would buy pages and put their club notes on there. Imagine a flier with kind of a sexy human posing next to a DJ, but digitized. It was the first kind of club flyers to be posted in the first versions of the internet, and radio was intertwined with that. Then internet radio happened, and I’ve just been fascinated by this my entire life. I love clubs, but I also like this side of it, the broadcasting side, which is a different mentality.

There’s a certain romance to the radio, which is that it’s there forever, sort of, and you’ve captured a certain feeling. Even when we look back to 2016, and we play back some of our first sets, we’re so nostalgic. We didn’t know what we were doing, and people have gone onto bigger and brighter things, as have we. That’s why it’s good to have recordings.

Yeah, I totally understand the romance of it.

Sometimes you feel like, “Is anyone listening out there?” But they are.

You guys are now known for throwing pretty unique parties, as well, like the jjimjilbang sauna rave last year. How do you usually come up with those ideas?

I think the first successful random event we did was at a Korean barbeque place. It was during COVID, and we were thinking, “What can we do that’s not a rave that’ll get shut down, and people will be apart?” The local barbeque place [Handoni] was struggling. It was a place where you’d always see the owners or promoters from the clubs hosting their guests of the weekend. It was funny, you’d be in there on a Friday and see Faust and their techno guests from Germany. It was quite healthy in a way, because it just showed what was happening that weekend in a microcosm, based on who was having dinner there. It took a while to persuade the ajumma [owner] about it, but by the end she was our emo [auntie] for the whole thing.

Then we got the bug for doing events in traditional Korean settings, with more modern music. We noticed that it got good reactions from everyday Korean people. I think in Korea, clubs do get kind of a bad rap. They’ve always been seen as not necessarily good for the public morale. To have a traditional club license is the same as the one for a go-go bar or something. But Korean people started to get it, they saw it’s just a party. We started to get picked up in more mainstream outlets.

It always gets brought up now, the barbeque rave or the sauna rave. [In the sauna rave] it was hard techno. It was 160 BPM gabber! I think you forget how fun dancing with bare feet is. We did that with Hajodaze [our beach festival in Yangyang] as well. Maybe we’re the barefoot party specialists.

I wanted to go to Hajodaze last summer, but Yangyang is pretty far from Seoul.

Yeah, there’s only one or two ways to get to Yangyang, and it’s usually a two hour drive [from Seoul]. But when everyone’s trying to get there, it’s maybe six, seven hours. There’s not many opportunities to party on a beach in Korea, because the military operates the beaches. I remember being at a beach party way back in 2015, and there was a North Korea siren. Suddenly the army propped up on the beach and set up position. There were crazy people in swimsuits that were taking pictures with a tank. The venue that we host Hajodaze at, [the owner] is an ex-army guy who has been into music, so he lets us use it. I should big up Juhwan [You] and Seulki [Lee], because they do a lot of hard work in talking to the older generation, and it’s gotten us some really nice events.

What are some newer challenges you’ve been facing as a station?

It's harder for radios to reach the people they want to run in a way that rewards the contributors. The way everyone consumes things these days is so homogenized. To do anything outside the box, they make it difficult. Even the web browsers are against us. You used to be able to run a third party player [on your site], like the way NTS does and many other radios. But you can’t do that anymore because Google is phasing out [sites] that autoplay [music], or it's seen as spam. I also think that they know it’s a way that people can host music. So it's really hard to run [your site like] old school internet radio. You don't really want to have [to build] all of that software yourself. You want to embed something else, like Airstream or Airplay, who already has the software. Twitch just got canceled in Korea as well.

Why did Twitch get canceled?

The operating costs are really high. The Korean government, as usual, has protectionist policies for Korean brands. You know [the South Korean streaming site] AfreecaTV? There’s that and Kakao and Naver, which they want to use as opposed to the international [platforms]. It makes me more emboldened to keep trying to do something independent from the big [corporations], because I feel like they just don’t want you to do it. I’m calling shenanigans on it.

You guys have kept things afloat for almost eight years now, but how do you feel about the sustainability of SCR and the independent scene in Seoul overall?

I tend to be quite positive, unless there’s a black swan event like COVID again. We did lose some venues sadly, but those guys came back with new ventures and revitalized in some aspects. There are a lot of new places opening all the time, and I see it all as being healthy. A lot more Koreans have traveled, and so I think they want institutions and clubs that are up there with what they’ve sampled out there in the world. The DJs who were the young kids eight years ago in 2016 are now growing up and want to start their own thing.

I also think the amount of producers coming out of Korea is really good, and because of K-pop, the production value is quite high. People study music quite hard, because they know if they can’t make money making hip-hop, techno, or house, they could still have a job in making K-pop. It’s almost like a career in music can be sustainable, even if you end up doing music you don’t particularly like. People don’t see the corporate and the underground as being enemies of each other anymore. If you do some good stuff in the underground, and the K-pop [companies] notice, or if you do a remix of NewJeans, and they post it, that could make your career.

As you’ve had conversations with other local community radio stations, is there something that’s come up frequently in your shared experience as station owners?

The thing that most people say keeps them going is the ability to bring through new interesting artists and give them a platform to shine. We all agree that it’s always great to see someone grow, like a kid with good ideas, or a female crew that’s shattered all perceptions in Korea, like Seesea’s crew. All of that is the rewarding stuff.