Heno. is donating 5% of all his 2023 releases to organizations fighting against the carceral state and recidivism. Learn more about The Bail Project, Maryland Alliance for Justice Reform, and Baltimore Action Legal Team here. TW: This article features recurring themes of death and incarceration.

Label execs can’t compete with Yihenew Belay’s secret weapon.

In Los Angeles, home to multi-million-dollar recording budgets, bidding wars, expensed signing dinners at Nobu, $11 lattes, and inhumane government failures to support the unhoused, an artist publicly known as Heno. works alongside his four-pawed co-producer, Mama. She once went by Jade. Heno.’s flatmates call the black cat Batman.

“Mama and her son Temi do their own thing, hiding out” Heno. tells us. “But when I’m working on beats? Mama knows to come right over and sits with me. If she’s wagging her tail, vibing, I’ll know that I should rap on it. I call her my A&R [Laughs].”

That feline sixth sense hasn’t hurt Heno.’s longstanding gift for wielding easy-on-the-ears melodies as deftly as abrasive rap attacks. When asked about his knack for wrapping hip-hop in pop, R&B, experimental, folk, drum n bass, and noise, he shrugs.

“Who wants to cook the same meals every day?”

Belay’s inner-universe features hydration dreams (a lifetime supply of Yerba mate) and optimistic framings of legal straits (“If they hit you with the paperwork, you know you’re sitting on fire”). A chunk of brain space goes to sprawling mental logs of deep musical vaults (“I’m working on 2024 records right now”). Aromas of home in the DMV, like onions and chicken absorbing berbere spices to summon doro wat, or hookah bars on U Street, never stray far from mind. Illustrious collaborators, from JPEGMAFIA and Mick Jenkins to Toro y Moi, make cameos, as do loving elders raising their eyebrows.

“I got uncles still asking me if I’m going back to school,” he says, smiling.

In conversation, Heno. seems to operate a zero-latency toggle, sharing hyperactive visions with sage calmness. The nomadic rapper-singer-producer exists within one of music’s in-between zones. A new face to many, an OG to others. Record deals on the table, independent by default. Grinding on demos in Brockton, Massachusetts with the Van Buren crew one week, rocking a Miami venue the next.

Heno.’s that rare artist capable of wide-ranging sonic hodgepodging and the crystal-balling of multiyear trilogies. Before COVID lockdowns, on the BART from Oakland to San Francisco, he outlined exactly that:

- Death Ain’t That Bad (Album; 2021)

- In the Meantime (EP; 2023)

- I’m Tired of Being Hypersurveilled (Album; TBD)

The prophecy’s held true. He delivered the first fragment on March 19, 2021, a self-produced testament to radical acceptance in the wake of loss. DATB’s highlights could win over the most skeptical crowds, from the Mos Def nod on the starting bars of “Blackstarrr” to the wistful longing for a better world on “Parallel Timelines”: “We wouldn’t have to trap / and the system would have our back / is it too much to ask for that?”

The album’s gut punch lands eight tracks in. “IDCAS,” acronym for “I don’t care about shit (that I can’t stay in control of),” compresses decades of simmering anger fueled by systemic bull shit into 1.5 minutes of vitriolic defiance. Like battling back legions of bloodhounds with a sampler. “This ain’t Drake with ‘Controlla,’” he snarls.

https://youtu.be/V1ysVm-4QAM“I was having a panic attack in my cousin’s house when I made that,” Heno. remembers. “Music is how I transmute what I can’t explain in words. Like scores for what’s in my head. I was repeating ‘I don’t care about shit I can’t control” to myself, like a mantra, yelling it over and over. I finally recorded it, put it in my sampler [starts mimicking drum machine movements] in Reason. It was some gnarly shit. But it felt empowering to flip such a painful moment into focusing on what I could control.”

That self-directed exorcism brought immediate relief to stress-swarmed nerves. It also illuminated the need to shoulder less weight, a process first sprouted by the passing of his brother, Addisu, in 2016. Heno.’s earned his lightheartedness. Peace through grief.

“I was pretty numb to it all until that,” Heno. says. “I took philosophy and religion in college. Most western thinking frames death as the mourning of a loss; in many other cultures, it’s the celebration of a legacy. For a long time, I felt like I couldn’t show I was struggling. I was learning how to speak at a funeral, how to carry a casket, looking after nieces and nephews. I have another brother who we couldn’t even tell for years. He was incarcerated and already going through that.”

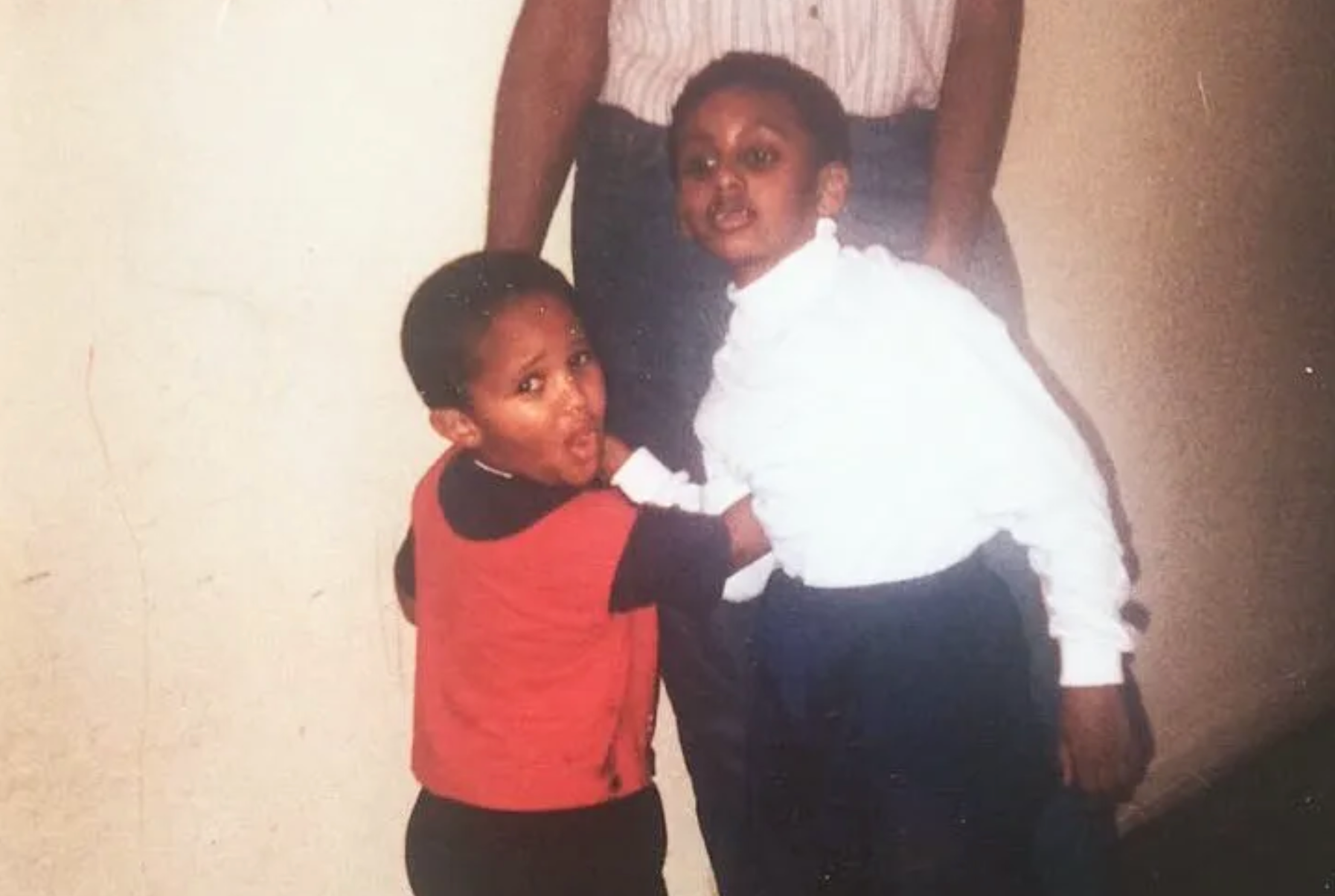

Six years later, Addisu’s spirit remains omnipresent. His influence on Heno. transcends genetics. Heno.’s parents loved music but discouraged creative pursuits. So many artists face this obstacle in their immigrant households that it’s practically a rite of passage. If not for a keyboard in Addisu’s home, and Addisu’s father offering warm encouragement, Heno.’s relationship with the piano might look different. Heno.’s trademark dreads, uncommon in traditional Ethiopian communities, follow Addisu’s example. Heno.’s mom saw Addisu pull them off and gave him the green light. And then there’s the video game they bonded over. These are Heno.’s artistic origins.

“Me and [Addisu] played Rock Band a lot. Like, a LOT bro. A LOT. The amount of money I spent unlocking songs from Led Zeppelin, Bob Marley... My brother would play guitar and I’d sing or play drums. We made a band in the game and played story mode and worked our way to stardom. From hole-in-the-wall venues to traveling in a van to flying to Europe. I’m wearing open buttoned-up shirts. At some point, it was like, what if we did this foreal? We ended up making a band, but it dissolved when no one showed up for the fourth session [Laughs]. Even still, I was enamored.”

Addisu’s support never wavered. A true ride-or-die from the very beginning.

“He was the first person I told I wanted to rap and didn’t laugh at me,” Heno. says. “He was posting my music on his Facebook in high school. Showing his friends my dumb freestyles. Later, when I was homeless, broke, kicked out of my parents’ house, he would take me to all of my studio sessions so I could finish the EP that ended up getting me noticed. We both were in sync about needing to expand beyond Maryland. He had lived in Zimbabwe, South Africa, Ethiopia. His worldview was so beautiful.”

The belief and pride Addisu placed in his brother even contributed to the stage name “Heno.,” a euphonic nickname used by family. This replaced Why-Fi, which spawned from the inability (or unwillingness) of teachers and classmates to pronounce Yihenew.

“My name was fucked up everywhere. Hanow, Yanow, Yahenu, Yahino... I’m one of the only Black people in my high-excelling classes, growing up in the projects with Black people, experiencing this cultural disconnect because I was born in America. Ethiopians didn’t accept me growing up, and Black people said I was Ethiopian, not Black. White people were like, ‘You’re not us!’ The cops taught me I was, in fact, Black by the time I was 4, 5, 6. I used to wish my name was Mark [Laughs].”

He fondly recalls the day a friend helped him change his Instagram handle to @mynameisheno, an act of reclamation, SEO just icing on the cake. It’s been a long road, and Heno.’s still in it for the long haul.

Some miracles work harder than others.

Prokaryotic bacteria wrote the blueprint for hustlers on planet Earth, surviving a volcanic hellscape to knock down the domino chain that led to you and me needing to grapple with strange concepts like “rent” and “Tucker Carlson.” Not even Master P, in peak tape-slinging form, could touch this single-celled drive. Before that, star dust, spiraling across interstellar enormity, activated evolution’s play button. The greatest band of all time isn’t the Beatles or Migos. It’s the trillions of commingling inputs required to create oxygen, and organs capable of inhaling and exhaling it. To witness any human being with a pulse is to witness the impossible. Trouble starts when manmade insidiousness makes some lives more impossible to live than others.

“I know what it’s like to have a knee on my neck, dragged by my hair, but I’m still here to talk about it, so no one knows about that,” Heno. tells us. “I’d be doing a disservice to my community to not be as candid as I am on record. It makes me hyper aware of how we’re monitored, how advertising is spun to be beneficial to us when it’s just making money off of these micro-analytics. It’s fatiguing, especially to marginalized people.”

In the United States, your odds of surviving child birth, let alone making it past 35, reflect centuries of actions and reactions that boil down to the presence of melanin in skin cells. Heno., a first-generation American born to Ethiopian-Eritrean immigrants, ticks this box. As such, Heno.’s guardian angel has gone on a dynastic run, winning heaven’s employee of the month again and again by keeping the Takoma Park, Maryland native alive every time he steps outside. Heno. has not forgotten the time his medication, “mistaken” for illicit drugs, led to him getting cuffed in 2nd grade.

“Life’s Too Short,” Heno.’s infectious 2021 record, features motivating vocals from Bianca Brown and a breakbeat synth-jazz outro that sounds like summertime grins. Across the song’s verses, he lampoons the perceived threat of a tall Black man by contrasting unfounded white fear with the statistical threat of medical malpractice during his mother’s (victorious) battle against colon cancer. Quite the A-B test.

The unbothered and insulated may sense a loosening grip on whatever convictions 2020/2021 tightened. If you went from rarely considering the cruel mechanics of ‘social norms’ (or thinking racism died in 2008) to noticing contrary evidence (and visible efforts to correct course, however half-hearted) more often, your eyes might roll in response to narratives of trial and trauma that suddenly feel, unfairly, overfamiliar. Whenever another marginalized story feels tired, it’s worth remembering that 99% of funded cultural works in the States have historically revolved around a white guy. As for the future, there’s vulture wet dreams like these to contend with:

What 2008 did teach us about representation, as meaningful as it is for millions, is that it alone cannot stop drones from turning blue skies in Syria into signals of terror. At least when it occurs within the confines of a white house in Washington. Nor can it narrow the racial income gap, protect affirmative action, or defeat the political stalemates imposed by a united coalition of people who undermined any attempt to recognize and respond to climate change, let alone the prison industrial complex. When representation bonds with strategic, progressive action, positive power results. This isn’t the task of any one person, but a collective fabric weaved by our choices.

To that end, Heno. has dedicated his time and earnings to battle recidivism (the repeat jailing of previous felons) and financialized imprisonment (pre-trial jail time predicated on whether an individual is wealthy enough to pay bail) in the DMV. Fundamental cogs of the stateside prison system’s entrapment cycle, recidivism betrays the fact that those fortunate enough to reenter society are set up to fail. Finding support for trauma during incarceration is hard and finding gainful employment with a tainted record is even harder. On the other end, bail creates a classist purgatory that robs lives, part of a broader issue of false imprisonment. (TW: The horrific treatment of the late Kalief Browder in New York’s Rikers Island jail offers just one example.)

Each of Heno.’s 2023 releases will allocate funds to The Bail Project, Maryland Alliance for Justice Reform, and Baltimore Action Legal Team. A three-part short film arriving this spring, belated support for In The Meantime, a four-song EP he shared last November and prophesied years earlier, is a PTSD-inspired psych thriller, brimming with easter eggs functioning as embedded collectables.

“Imagine The Sopranos, but Tony can actually tell his therapist what’s going on,” Heno. says.

His next full-length, trilogy closer I’m Tired of Being Hypersurveilled, will touch down at an apt time. Nextdoor and Ring have tag-teamed to unlock the (barely) repressed vigilante spirit of suburbia while police funding distinguishes itself as the only thing that’s actually recession proof.

“I’m at a point where I know it’s okay to not be okay, and to take grace for yourself,” he says. “When I do get into a mode of not knowing if I can get through something, I think of my brother. I still act like he’s right there with me. And nothing is worse than losing him. So that changes my perspective on what an L is, because I know real loss.”

Death powers Heno.’s relentless drive for life. He has no problem acknowledging what’s destined. To pretend otherwise is to live in fiction. Loss has set him free. Playing sidekick to this innate propellant is liquid energizer, served in a small cup.

“Coffee is a ritual in our culture,” Heno. says, cheerful. “You sip from a cini, and you sip for hours, sitting down and sharing stories together, often wearing gabbis, which are like super comfortable Ethiopian cloth blankets. It’s ceremonious, poured from jebena, a special coffee pot. When we roast coffee beans, you bring the beans to each person you’re with at that moment, and they give thanks. It’s like a blessing.”

At the end of our interview, Heno. jumps into his best Jadakiss impression, reenacting the New York icon’s legendary VERZUZ moment that pit him and The LOX against Dipset’s Cam’ron and Jim Jones. Kiss reaffirms his undying loyalty to New York and dares anyone doubting his neighborhood ties to come see him outside. From Jay Z’s 4:44 to the otherworldly Andre 3000 guest features that rise from the ether, it presented another hip-hop great aging gracefully, still committed to their craft. This is the longevity Yihenew Belay trains for.

“Artists should be getting better as they get older,” he says. “I’m going to make better music in five years than I am right now. I’m still as hungry as I was when I first started. I’m starving. And I want to be starving when I’m 40. Writing like I got rent due tomorrow. People only know what you tell them. They don’t see you working in the dark.”

Heno. is donating 5% of all his 2023 releases to organizations fighting against the carceral state and recidivism. Learn more about The Bail Project, Maryland Alliance for Justice Reform, and Baltimore Action Legal Team here.